Fragility

When I think of fragility, I immediately picture someone with no skin — open, exposed, absorbing everything. Someone who’s life has been torn apart — literally or metaphorically. Someone vulnerable. But then again, all people are fragile and vulnerable in their own way.

I will be thinking about this word in the art context, and I want to talk about several works that struck me profoundly. I am impressionable and fragile myself in this sense — so much so that while searching for examples, I stumbled upon certain pieces and am still recovering. I will write about some of them. Others I will not, because it’s too heavy.

Yet despite everything I described above as my own feeling of what this word means, I believe that after such moments people become stronger. We have to survive every «fragile» period in our lives, because it will lead somewhere — good or not so good, but still, we move forward. This matters. We will probably change along the way, but in my understanding this is what life is: breaking, gathering yourself, moving on — only to perhaps repeat these same actions in a different context.

This is why I find the concept of fragility in art so compelling. These artists do not depict fragility as victimhood or weakness. They activate it — as a gift, as a trace, as a form of presence that persists even as it disappears.

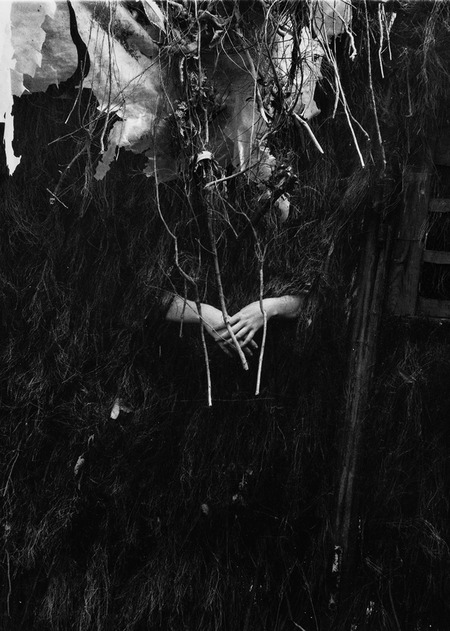

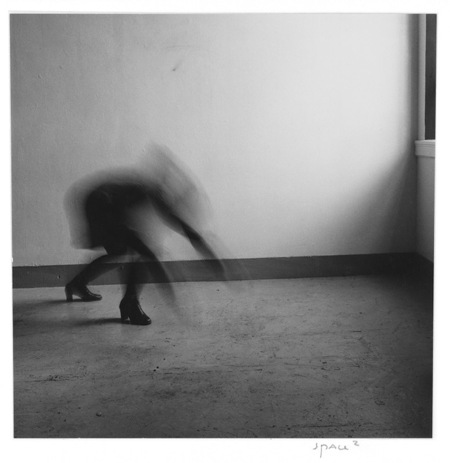

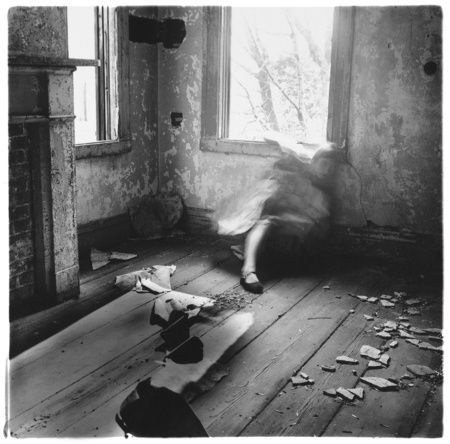

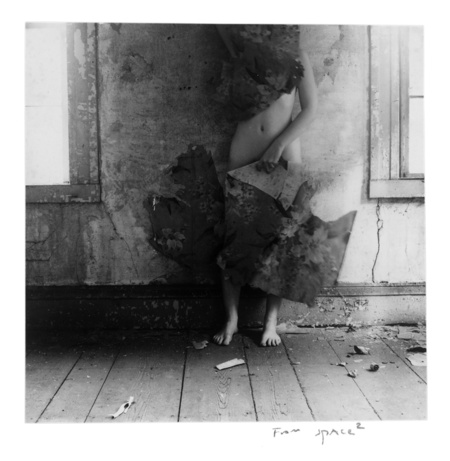

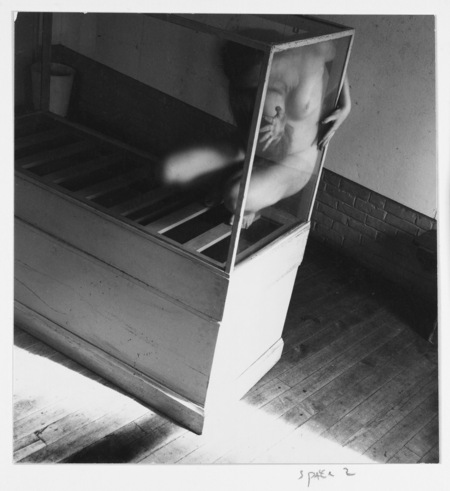

Francesca Woodman — «Space2» (1976)

Francesca Woodman, From Space2, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976 © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Francesca Woodman was eighteen when she made these photographs — images where she appears and disappears, using long exposures to turn her own body into a blur, a smear, a ghost caught mid-motion.

Her work struck me deeply. She morphs into the space around her, as if wanting to evaporate and dissolve into it, or perhaps leave a trace. She took her own life at the age of 22, and looking at her photographs, I feel that I can see this pain: the desire not to exist, to dissolve into the surroundings. It’s essential to me that she’s the one breaking down the fragile wall between herself and space — she is trying to merge with it, to become it’s inseparable part. The world is not pulling her in.

Her work gets you wondering: what if fragility is not about being broken, but about being permeable? What if the human body itself is not a fortress but a threshold?

Francesca Woodman, From Space2, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976 © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ana Mendieta — «Silueta Series» (1973–1980)

Ana Mendieta, Imágen de Yágul, Untitled, from the Silueta series, 1973, chromogenic print, 50,8×35.3 cm (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection

It was Ana Mendieta’s «Silueta Series» that made me feel deeply and think about things I had never considered before. Mendieta was twelve years old when she was sent away from Cuba to the United States as part of Operation Pedro Pan — a program that evacuated over fourteen thousand children during the early years of Castro’s regime. She never fully returned. Her art became a way of returning — not to a place, but to the earth itself.

She left her silhouettes in the ground, on sand, on rocks, on fabric — using blood-red paint, fire, flowers. And the first thought that comes to mind is that all of this will come to an end. The earth will grow over with grass and flowers, the water will wash everything from the sand, the rocks will erode, the fire will burn out, the flowers will wilt. I find this to be a powerful message. The fragility of the body, of nature, of time — everything comes to an end, and to a new beginning. In this vulnerability lies the value of human life itself.

In her work, fragility is shown not as brokenness but simply as a condition. She left a mark knowing it will vanish, and all that remains of these works are photographs. I find this deeply courageous.

Ana Mendieta, Anima, Untitled, from the Silueta series, 1976 (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.), (The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles) © The Estate

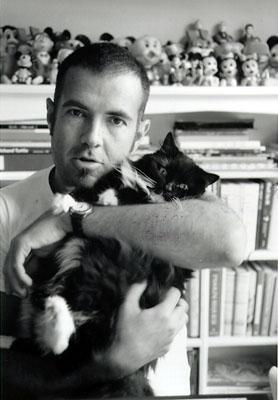

Felix Gonzalez-Torres — «Untitled» (Revenge) (1991)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Traveling, Installation View, 1994.

In 1991, Felix Gonzalez-Torres filled a gallery floor with blue candies. Visitors were invited to take one. The pile diminished over time — its clean, minimalist edges dissolving into rivulets and scattered pieces.

Gonzalez-Torres explored the fragility of the human body through his art. He lost his partner to AIDS, and the disease would take him five years later. The weight of the candy exactly matches the body weight of someone he loved. To take a candy is to participate in a symbolic depletion — to take a small piece of a body that is dying.

But why candy? Because there’s no guilt in this gesture. Gonzalez-Torres offers his fragility as a gift. The sweetness is real. The loss is real. Both exist at once. In a moment of losing someone, one could easily turn to aggression and pain — but he offers something else: to be human, to be present, to be near.

The title — «Revenge» — is unexpected. Revenge against what? Perhaps against a system that let so many die. Perhaps against the idea that fragility is shameful, something to hide. By making his grief public and participatory, Gonzalez-Torres refuses the isolation that illness imposes. He builds a community around loss.

This is fragility not as weakness, but as radical openness. An invitation to share something very difficult and intimate.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Traveling, Installation View, 1994.

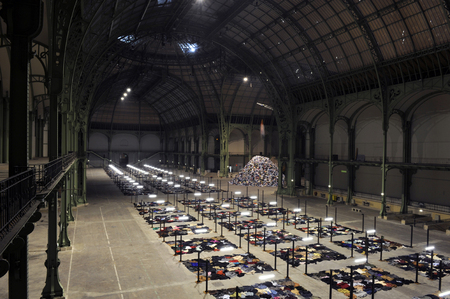

Christian Boltanski — «Personnes» (2010)

«PERSONNES» por Christian Boltanski. Monumenta 2010. Fotografía por Didier Plowy | «PERSONNES» por Christian Boltanski.

In 2010, Christian Boltanski filled the Grand Palais in Paris with the clothes of the dead. Tens of thousands of garments were laid out in neat rectangles across the vast floor — like bodies, like graves, like a census of the absent. At the center, a mountain of clothes rose toward the glass ceiling. A mechanical crane moved ceaselessly above it, picking up random handfuls and dropping them back down. The space was cold — the heating had been deliberately turned off. A rhythmic sound of heartbeats echoed through the hall. Visitors walked among the garments, dwarfed by the scale of accumulation.

This installation makes you think about the fragility of the individual before a system. Each of these garments belonged to someone, yet the mechanical crane selects its «victim» at random and tosses it somewhere into the distance. Because of the sheer quantity of things, the very idea of individuality disappears — it all merges into something singular and mass.

Boltanski often spoke about the Holocaust, though his work is never literal about it. «Personnes» evokes the piles of belongings left behind in concentration camps, but also any catastrophe — natural, political, medical — where individuals become statistics. The crane’s random selection suggests the arbitrariness of fate: who lives, who dies, who is remembered.

This is also about the fragility of individuality itself. After mass death, what remains?

«PERSONNES» por Christian Boltanski. Monumenta 2010. Fotografía por Didier Plowy

Berlinde De Bruyckere — «Cripplewood» (2013)

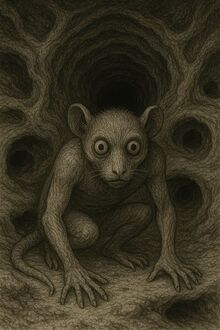

Berlinde De Bruyckere — «Cripplewood» (2013)

For the Belgian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale, Berlinde De Bruyckere brought in a fallen elm tree — enormous, ancient, uprooted. But she did not leave it as she found it. She covered it in wax, wrapped it in cloth and leather, bandaged its limbs. The tree, laid out in the neoclassical space, looked like a body on an operating table. Or a corpse being prepared for burial.

The title refers to Dante’s Inferno — specifically, the forest of suicides in the seventh circle of Hell, where the souls of those who took their own lives are imprisoned in trees. When the branches break, the trees bleed and speak. They are trapped in a form that cannot die.

This is one of the works that put me in a vulnerable state. When I first saw it, I did not realize it was a tree — it looked like some part of a leg, a limb. Reading more about it, learning about the reference to Dante, cast it in a different light. The tree truly looks as if it is suffering, as if something is terribly wrong, as if it is in pain.

This work takes the term «fragile» completely out of the context of the human and the human body. It reminds us that everything around us is fragile.

Berlinde De Bruyckere — «Cripplewood» (2013)

Conclusion

Each person sees the world differently because of their own life experience — and this is the very value of being human:having the ability to share it, to show what the world looks like through your eyes.

These artists reveal the term «fragility» from different angles, yet in the context of this word, they are all united by something — pain, loss, and a desire to do something with it, even if that something is simply showing it to the world and sharing a message. Woodman dissolves into space, Mendieta returns to the earth, Gonzalez-Torres offers his grief as candy, Boltanski lays out the clothes of the anonymous dead, De Bruyckere bandages a wounded tree. Each of them found a way to make fragility visible — not as something to overcome, but as something to inhabit and transform.

In the process of writing this essay, I had the chance to look at this word from different perspectives and to encounter breathtaking artists who shifted how I see certain things, or showed me a perspective I had never considered. I would say that all of them were processing their emotions through these works — working through fragility by making it into art.

At the beginning, I wrote that life is about breaking, gathering yourself, and moving on. I still believe this. But now I would add: sometimes the breaking itself becomes the work. And in sharing it, we become a little less alone.

Badovinac, Z., Carrillo, J., & Piškur, B. (Eds.). (2018). Glossary of common knowledge. Moderna galerija.

Badovinac, Z., Carrillo, J., Hiršenfelder, I., & Piškur, B. (Eds.). (2022). Glossary of common knowledge 2. Moderna galerija.

Boltanski, C. (2010). Personnes [Installation]. Grand Palais, Paris, France.

De Bruyckere, B. (2013). Kreupelhout — Cripplewood [Installation]. Pavilion of Belgium, 55th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy.

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. (2015, November 25). Christian Boltanski—Anselm Kiefer by Irina Kulik. https://garagemca.org/en/event/christian-boltanski-anselm-kiefer-by-irina-kulik

Gonzalez-Torres, F. (1991). «Untitled» (Revenge) [Candy installation]. Collection of Barbara and Howard Morse.

Güner, F. (2018, December 15). A Q& A with Berlinde De Bruyckere. Fisun Güner. https://fisunguner.com/a-qa-with-berlinde-de-bruyckere/

Mendieta, A. (1973–1980). Silueta series [Earth-body works]. Various locations.

Moderna Museet. (2016). Francesca Woodman: On Being an Angel [Exhibition]. Moderna Museet Malmö. https://www.modernamuseet.se/malmo/en/exhibitions/francesca-woodman/

Renaissance Society. (1994). Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Traveling [Exhibition]. University of Chicago. https://renaissancesociety.org/exhibitions/392/felix-gonzalez-torres-traveling/

Smarthistory. (n.d.). Ana Mendieta, Silueta series. https://smarthistory.org/ana-mendieta-silueta-series/

S.M.A.K. (2013). Biennale di Venezia — Pavilion of Belgium in Venice: Berlinde De Bruyckere, Kreupelhout — Cripplewood [Exhibition]. https://smak.be/en/exhibitions/biennale-di-venezia---paviljoen-van-belgie-in-venetie

Woodman, F. (1976). Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island [Photograph].

Woodman Family Foundation. (n.d.). Francesca Woodman. https://woodmanfoundation.org/

https://woodmanfoundation.org/artworks/untitled-5591 (accessed 09.12.2025)

https://woodmanfoundation.org/artworks/space2-3 (accessed 09.12.2025)

https://woodmanfoundation.org/artworks/space2-4 (accessed 09.12.2025)

https://woodmanfoundation.org/artworks/from-space2 (accessed 09.12.2025)

https://woodmanfoundation.org/artworks/space-2 (accessed 09.12.2025)

https://woodmanfoundation.org/artworks/house-3 (accessed 09.12.2025)

https://smarthistory.org/ana-mendieta-silueta-series/ (accessed 09.12.2025)

https://www.wikiart.org/en/felix-gonzalez-torres (accessed 09.12.2025)

https://renaissancesociety.org/exhibitions/392/felix-gonzalez-torres-traveling/ (accessed 09.12.2025)

https://artreview.com/christian-boltanski-whose-art-probed-mortality-and-memory-has-died-at-76/ (accessed 09.12.2025)

https://www.metalocus.es/es/noticias/personnes-en-monumenta-2010 (accessed 10.12.2025)

https://garagemca.org/en/event/christian-boltanski-anselm-kiefer-by-irina-kulik (accessed 10.12.2025)

https://fisunguner.com/a-qa-with-berlinde-de-bruyckere/ (accessed 10.12.2025)